Chinese Drywall: What Homebuyers Need to Know Before Making an Offer

If you’re shopping for a home built or heavily renovated in the mid‑2000s, especially in the Southeast and Gulf Coast, you may run into a term that stops you in your tracks: Chinese drywall. It’s a real issue with real financial and health implications, but it doesn’t have to derail your home search. With the right questions, inspections, and contract protections, you can move forward confidently—either with the home you love or with the clarity to walk away.

What “Chinese Drywall” Means—and Why It Matters

Chinese drywall typically refers to certain gypsum wallboard imported from China and installed in U.S. homes roughly between 2001 and 2009, with a peak in the mid‑2000s when hurricane rebuilding and a construction boom created material shortages. Investigations by government agencies and building experts found that some of this drywall emitted sulfur gases that can corrode metals and create a persistent “rotten egg” smell. Not every sheet of drywall imported from China was defective, and not every home built during those years is affected. But when the problem is present, it can damage copper wiring, air conditioning coils, plumbing components, appliances, and electronics—and that raises safety, cost, and livability concerns.

From a homebuyer’s perspective, the stakes are straightforward. A home with confirmed defective drywall may be hard to insure, hard to finance, expensive to fix, and, until remediated, potentially unsafe. Your job during due diligence is to determine whether the home is impacted, whether it has been properly remediated, and what protections you need in your contract and financing to manage the risk.

Where and When to Be Extra Vigilant

Chinese drywall issues showed up most often in Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, the Carolinas, and parts of the Mid‑Atlantic, particularly in homes built or renovated between 2004 and 2008. That said, drywall moves with supply chains, so the only reliable approach is to look at the specifics of each property rather than relying solely on location or build year.

If you’re touring a 2006 townhouse in Tampa, a 2007 single‑family home near New Orleans, or a condo in coastal Virginia with a renovation permit from 2005, the risk profile is higher. But even a 2003 or 2010 property with substantial drywall replacement during those years is worth a closer look. Always check the building permits and renovation history when you can—your agent can often pull these, and many municipalities make them public online or in person.

Early Red Flags You Can Notice Without Tools

You won’t diagnose Chinese drywall by sniffing around, but early observations can help you decide whether to invest in specialized inspections. A strong sulfur or “rotten egg” odor is one clue, though absence of odor doesn’t mean you’re in the clear. Look at exposed copper where you can see it—behind the HVAC air handler panel, at the refrigerator water line, under sinks, or at electrical ground wires in the panel (only if the panel is safely accessible). Blackened or heavily tarnished copper, repeated failures of air conditioning coils, and premature corrosion on metal surfaces can point to trouble.

Be aware that normal aging, high humidity, or previous water damage can also corrode metals. That’s why these early observations should lead to a proper inspection rather than to conclusions. If something feels off—like a 5‑year‑old condenser coil that has already been replaced twice—flag it and plan to go deeper during the inspection period.

How to Vet a Property During the Inspection Period

A standard home inspection is a smart start, but Chinese drywall calls for a more targeted approach. Ask your inspector directly whether they have experience identifying signs associated with corrosive drywall. If not, bring in a specialist such as a licensed building consultant, environmental engineer, or contractor with documented expertise in this issue.

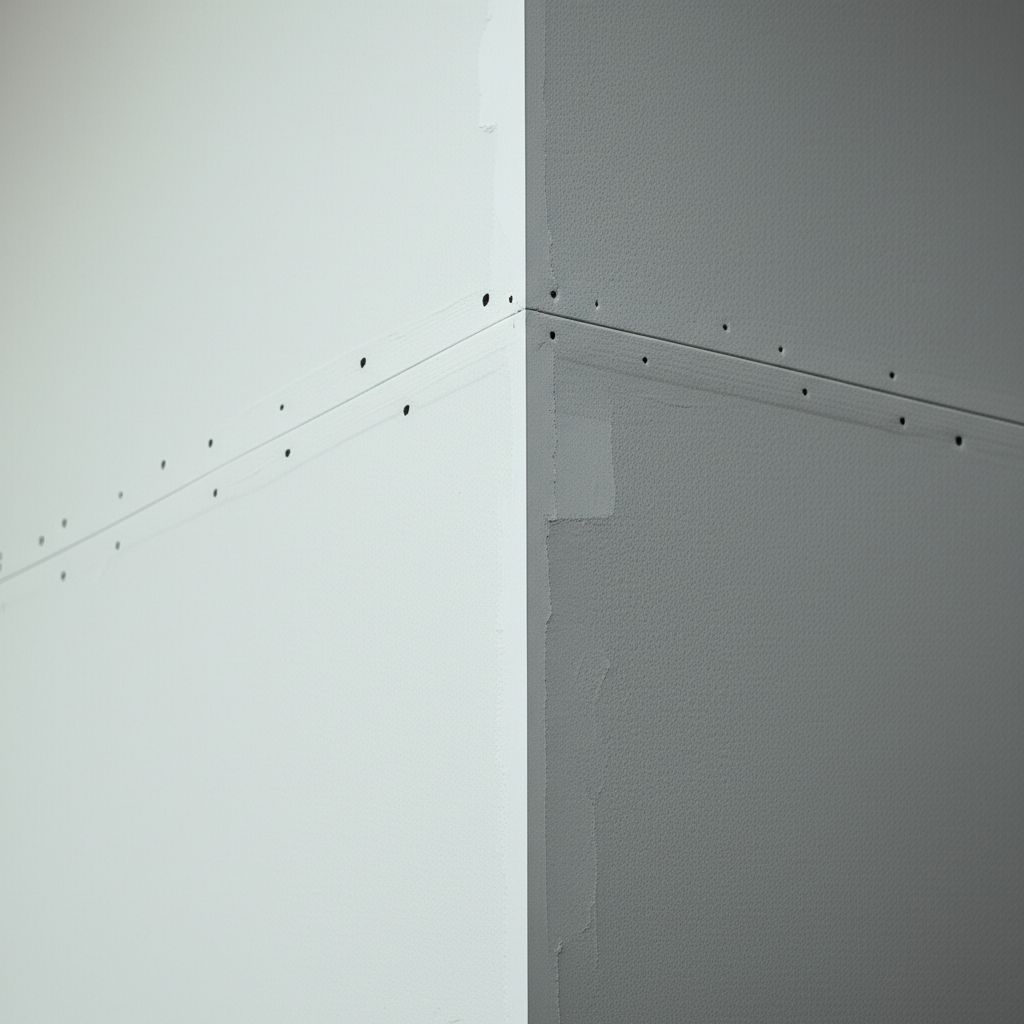

Inspection often follows a layered process. First, a visual assessment looks for widespread copper corrosion, pitting on mirrors and chrome finishes, blackened air conditioning coils, and tarnished copper wiring at outlets and in the electrical panel. Next, experts may look for labeling on the back of drywall sheets, which requires selective, careful removal or access through attic spaces; some batches have identifiable manufacturer stamps or markings. Where uncertainty remains, sample testing by an accredited lab can analyze drywall for markers commonly associated with problem batches. Your goal isn’t to become the lab technician—it’s to obtain a clear, written opinion from a qualified professional that can inform your negotiations and your lender’s decision.

Build a little extra time into your inspection contingency for this work. Instead of the typical one‑week window, aim for 10–20 days to coordinate specialists and potential lab turnaround. The “inspection contingency” is the clause in your purchase contract that lets you cancel or renegotiate if you uncover defects. Without enough time, you may end up waiving your right to act on new information.

Understanding Paper Trails and Proof of Remediation

Many affected homes have been remediated. That’s encouraging—when done properly, remediation can restore a home’s safety and value. But the quality of the fix hinges on what was removed and replaced, who did the work, and how it was documented. A true remediation typically involves taking out all problem drywall, replacing affected copper components like electrical wiring, outlets, switches, and HVAC coils, swapping out corroded fire safety devices such as smoke alarms, and then rebuilding to current code.

When a seller claims remediation, ask for the full package: permits, scope of work, contractor licenses, invoices, city or county final inspections, and any third‑party clearance or certification letters. Look for dates that align with the work, not just a one‑page statement. If there was a builder or manufacturer settlement, there may be documentation and warranties attached to the property. Independent verification by a consultant gives added peace of mind, especially if the remediation occurred years ago or if multiple owners have come and gone.

Financing and Insurance: Why Pre‑Approval Isn’t Enough

A conventional pre‑approval letter shows you qualify for a loan, but lenders still need to approve the specific property. Appraisers consider health and safety issues, and many lenders will not fund a loan on a home with confirmed defective drywall unless remediation occurs before closing. Government‑backed loans such as FHA and VA typically require that the property be safe, sound, and secure; if Chinese drywall is present, those loans will almost certainly require correction first.

There’s a workable path if you love a property and it needs remediation. Renovation loans, such as an FHA 203(k) or conventional renovation products, can finance the purchase and the repairs in a single mortgage. You’ll need a detailed contractor bid and an appraisal of the “after‑improved” value. The lender will release funds in stages, and you’ll likely work with a renovation loan consultant to oversee draws. The tradeoff is more paperwork and time, but it can transform a distressed asset into a solid home.

Insurance is the other piece. Some insurers are wary of homes with a history of corrosive drywall, even after remediation. Before you remove contingencies, secure a written binder from your insurer confirming coverage and any exclusions. If your current carrier won’t bind, your agent can obtain quotes from specialty carriers. Don’t assume that because a neighbor insured their home, yours will be automatic; underwriters make case‑by‑case decisions based on documentation and condition.

Contract Protections: Contingencies, Earnest Money, and Escrows

A clear contract gives you leverage and options. Your “earnest money” is the good‑faith deposit you put down when your offer is accepted. It’s usually held by a neutral party and credited to you at closing. It can be refundable if you cancel within your contingency periods for valid reasons, like an inspection finding. The “inspection contingency” gives you a time window to investigate and either move forward, renegotiate, or cancel. A “financing contingency” protects you if your lender won’t approve the loan on the property. An “insurance contingency” can be added to ensure you can bind acceptable coverage.

If testing reveals issues, you generally have three paths. First, the seller can remediate before closing, with licensed contractors and inspection sign‑offs, after which you proceed. Second, you can negotiate a price reduction that fully covers the cost of remediation and related expenses such as temporary housing and a contingency buffer. Third, you can set up an escrow holdback, where a portion of the seller’s proceeds is held by a neutral escrow company and released only when the work is completed and independently verified. “Escrow” simply means funds are held by a trusted third party until certain conditions are met. If you go the holdback route, make sure the amount is realistic for a full gut of affected drywall and replacement of impacted components, not just a cosmetic patch. Remember that quotes can vary; building in a margin helps avoid last‑minute shortfalls.

A Real‑World Scenario

Imagine Maya and Andre, first‑time buyers relocating to the Gulf Coast. They fall in love with a 2006 townhome—great layout, perfect location. During their tour, they notice a faint sulfur smell in the utility room and a note on the kitchen counter about a recently replaced A/C coil. Their agent recommends extending the inspection period to 15 days and bringing in a specialist. The inspection reveals significant copper corrosion and labeling on accessible drywall that matches documented problematic lots.

Armed with a detailed remediation estimate and a lender familiar with renovation loans, Maya and Andre have options. The seller declines to remediate pre‑closing but agrees to a substantial price reduction and an escrow holdback at closing. The buyers switch to an FHA 203(k) loan, lock in an insurance binder contingent on completion, and move into a short‑term rental during the work. The project includes removing all affected drywall, replacing electrical components and HVAC coils, and rebuilding to current code. Three months later, they receive a third‑party clearance letter and their escrow funds release to the contractor. Was it more complex than a typical purchase? Yes. But with planning and protections, they turned a risky property into a safe, updated home within budget.

Condos and HOAs: Extra Layers to Consider

In condominiums and townhome communities, responsibilities are split between unit owners and the association. Drywall on the interior side of your unit is often your responsibility, while drywall bordering common areas or structural elements may fall to the association. Corrosion can affect shared systems, too, such as fire suppression or building‑wide HVAC components. Before you commit, review the association’s disclosures, minutes, and financials. Look for past or pending special assessments and any mention of corrosive drywall. Ask whether other units were remediated and how the association handled it. Even if your unit appears clear, a poorly funded HOA facing widespread remediation can hit owners with assessments later.

Health Considerations—And Staying Within Your Lane

Homebuyers often ask whether Chinese drywall is a health hazard. Reports have included irritated eyes, skin, and respiratory symptoms in some occupants, along with headaches. The most consistent, scientifically verified concern is damage to copper and other metals. Because people’s sensitivities vary, consult a licensed environmental professional and your healthcare provider if you have specific concerns. From a purchase standpoint, focus on verifiable building impacts and documented remediation; those are the elements that affect financing, insurance, and long‑term value.

Costs, Timelines, and Living Through Remediation

Remediation costs vary widely with the size and complexity of the home. For a modest single‑family property, it can run from tens of thousands of dollars to six figures, especially when you factor in replacement of electrical wiring, outlets and switches, HVAC components, and non‑recoverable finishes. Full removal is invasive. Expect to move out, protect or store belongings, and allow time for inspections and permits. The upside is that you often end up with updated systems, new finishes, and a home that meets current codes. That can be a value win if the purchase price reflects the true scope of work.

If a Home Has Already Been Remediated

A properly remediated home can be a smart buy, but treat it like any other major repair: trust, then verify. Review permits, contractor credentials, invoices, and final inspection reports. Look for a third‑party clearance letter and any transferable warranties. Have your inspector check for lingering corrosion or mismatched areas that suggest partial work. Confirm that permits were closed. Lenders and insurers will ask for the same documents; having them assembled early helps your closing stay on track.

Negotiating With Confidence

When you bring a calm, informed approach to the table, you stand out as a serious buyer. Sellers may be defensive or unaware; keep the conversation factual and solution‑oriented. Share inspection findings, bids, and lender requirements. Propose concrete paths forward—seller remediation before closing, a price adjustment that reflects the full scope and a buffer, or an escrow holdback with clear milestones. Tie every request to a rationale a seller can accept: the lender won’t fund without resolution, the insurer won’t bind, or the appraiser requires correction. That clarity often leads to agreement even in tense situations.

The Bottom Line for Buyers

Chinese drywall is a manageable risk when you know how to approach it. Start with smart screening based on build or renovation years and location. Use a robust inspection strategy with specialists and, when appropriate, lab testing. Secure financing and insurance that match the property’s condition, and build contract protections—inspection, financing, and insurance contingencies, plus escrow if needed—so your earnest money stays safe. If problems arise, you can walk away, negotiate from strength, or finance a proper fix and end up in a home you love.

Buying a home is never about eliminating risk altogether; it’s about understanding it, pricing it, and protecting yourself along the way. With the right team and a clear plan, even complicated issues like Chinese drywall don’t have to stand between you and a successful purchase.